This book came on my radar through fellow international bibliophile Suroor Alikhan, who kindly hosted me at an online event organised by the Hyderabad Literary Festival last year. A few weeks ago, she contacted me saying that she had found a website that she thought I’d be interested in, featuring a list of more than 100 books by Pacific Islanders.

I was intrigued. The Pacific Island nations were among the most difficult countries to source stories from during my 2012 quest to read a book from every country. And although the criteria of the list’s compiler were a little different from mine – she included a number of titles by writers with Pacific Island heritage (including herself) – there were many fascinating-sounding works.

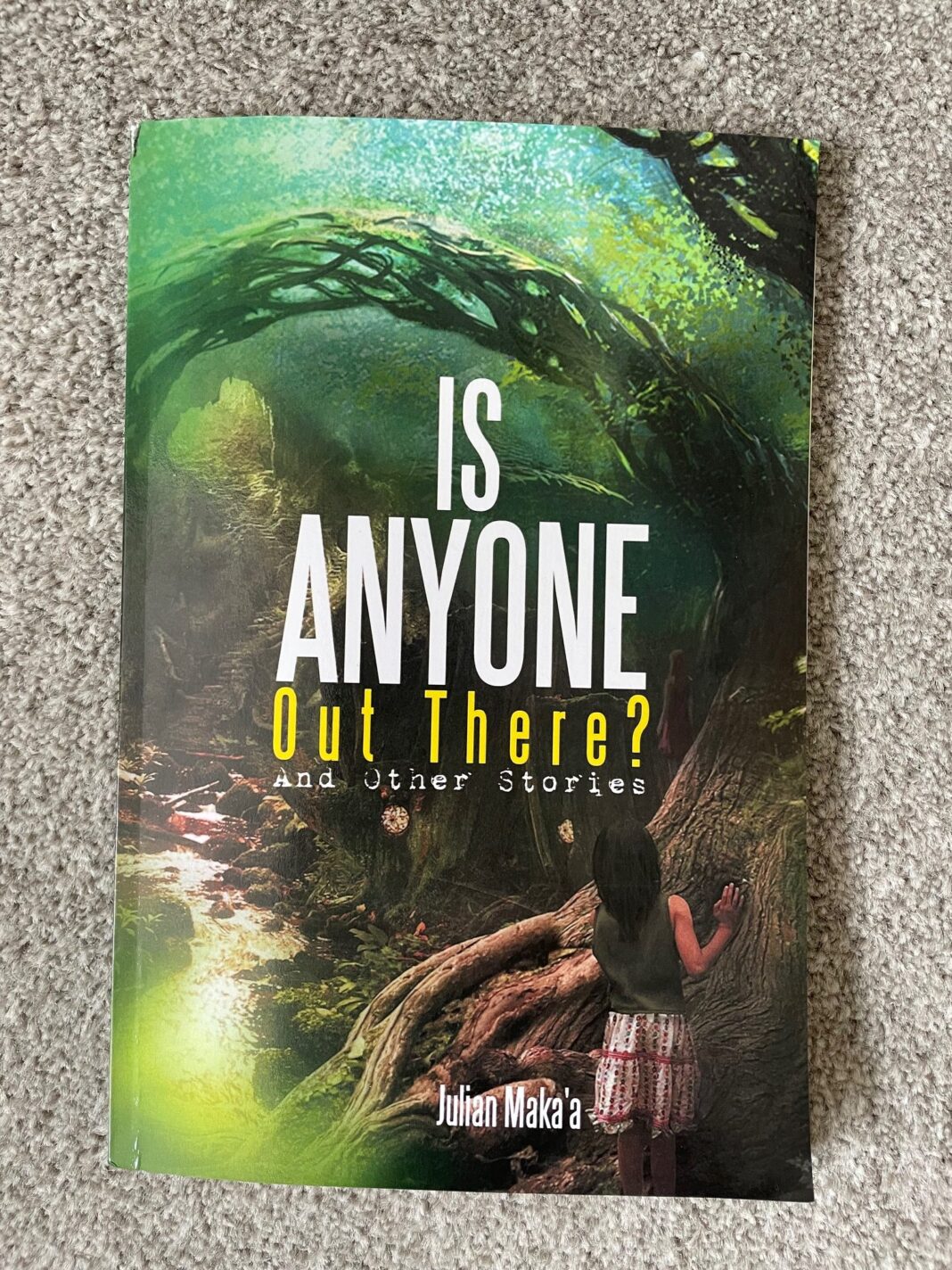

The book I’ve picked to feature – Is Anyone Out There? And Other Stories by Julian Maka’a from the Solomon Islands – didn’t strike me as the most satisfying of those I read from the list, but I found it interesting for several reasons.

The Solomon Islands are hard to source stories from: back in 2012, the best option I could find was The Alternative, a 1980s boarding school novel. So I was curious about what this much more recent short story collection would be like.

My interest was also piqued by Maka’a’s statement on the back cover that the collection – which he self-published in 2012, 27 years after his first collection was brought out by the University of the South Pacific – draws on various aspects of his professional life, including efforts to build staff understanding about sexual reproductive health in his capacity as the manager of Wantok FM, part of the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation. This is reflected in frank descriptions of the treatment of and stigmas around sexually transmitted diseases in several of the earlier pieces.

As with many of the books I read ‘from’ Pacific Island nations in 2012, the collection seems written with a consciousness of needing to represent its nation. ‘The themes and general messages [of the stories] are different and varied,’ writes Maka’a, ‘but the one thing that is common is they reflect what life is like in Solomon Islands’.

To an outsider like me, this manifests itself most tellingly in the glimpses into local beliefs and customs, presented most richly in the title story, in which a legend about a philandering man ritually killed for breaking taboos haunts the narrator.

The emphasis on education, so apparent in The Alternative, is also strong in Maka’a’s work. The most ambitious piece in the collection, a three-part story called ‘Is This Fair?’ centres on a teenage pregnancy at a boarding school and makes clear the sacrifices that the nation’s geography and economic situation demand of families keen to give their children opportunities. Some eight thousand students drop out of education every year, we learn, and just getting to school at the start of term often requires many stomach-churning hours in a boat.

As is so often the case in books from elsewhere, it is the assumptions and things taken for granted that prove most intriguing. One of the central characters in ‘Is This Fair?’, for example, seems not to bat an eyelid at the notion that her parents will decide her career path, as set out in a letter her mother sends her:

‘In her brief letter which she wrote in language and pijin, she explained that she and dad always discussed about me. About the future that I would give them from my education – benefits to cut a long story short. She said they had differences in the job I should take up after I graduate in form five. My mother said she wanted me to become a nurse – that way I would help her when she gets sick or even my father. My father on the other hand wanted me to be a teacher.’

For all its interest, however, this book is a challenging and occasionally bewildering read. My knee-jerk reaction is to pin this on the fact that it has probably not been through the editorial processes of many traditionally published books in mainstream anglophone literature, with the result that there are structural idiosyncrasies, and spelling and grammatical oddities that are sometimes distracting. There seem to be some inconsistencies in the character names between the different parts of ‘I Am Fair?’ that make it hard to follow. There is also an abruptness to certain emotional shifts and transitions that risk interrupting the flow of the story.

But I’m also aware that what I read as errors or idiosyncrasies may in many cases not be considered as such by readers in the Solomon Islands. There, a different form of English is used, one in which certain formulations and word uses that sound odd to me may be customary. Similarly, shifts between registers and emotional states that jar for me may simply reflect different norms or storytelling traditions beyond my experience feeding into this book.

Regardless of how I read it, what remains is a sense of urgency. A desire to communicate. A hand stretched out from this place we in the UK rarely hear of, seeking connection and the chance to convey something. This is me, this book says. This is us. This is where we are.

Is Anyone Out There? And Other Stories by Julian Maka’a (Xlibris, 2012)